The Writer vs. the Shinyperfect

/The saying is “The perfect is the enemy of the good,” but for our purposes it might be better to think of it as “The idea of the perfect is the enemy of the good.” I am referring of course to the Lichtenbergian concept of shinyperfect, that insidious trick of the brain of coming up with a “perfect” idea and then handing it off to you to turn into a real thing.

That’s when you find out that your brain has lied to you. The idea is not perfect. It’s barely an idea, just a shimmering mirage of that perfect novel/song/painting. And now you’re stuck with this piece of crap that simply won’t create itself.

I am currently working with three writers, each of whom has a really good shinyperfect for a book but none of whom has seriously started committing those thoughts to paper. Interestingly, all three acknowledge that all they need to do is start scribbling ideas down willy-nilly, and yet they have not yet done so.

The problem seems to be that they understand at some level that what’s in their head is not even close to a real thing and to make it real will mean a lot of hard work. So let’s look at how “real” authors do it.

We’ve seen the Dostoevsky manuscript before:

What a mess! When you’re writing an actual Russian novel, it’s probably going to look a lot like this as you juggle all those characters and settings and themes.

But even the tidy Miss Jane Austen…

the manuscript for austen’s unfinished novel, “Sanditon”

…found it necessary to correct and amend and edit.

And my work? Exemplary:

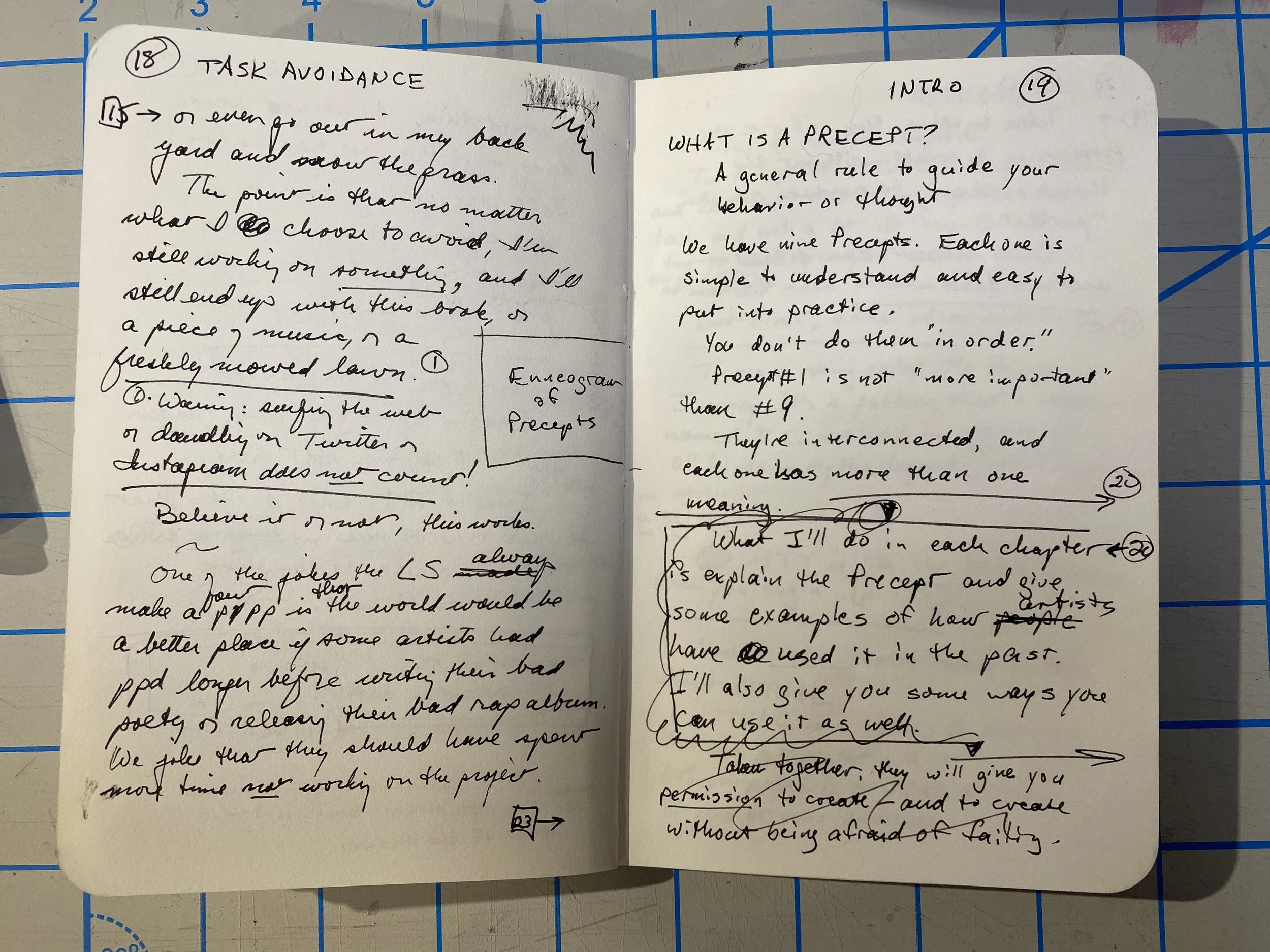

manuscript of “A Young Person’s Guide to Lichtenbergianism”

I land somewhere between Austen and Dostoevsky, at least in terms of chaotic transcription styles.

This concept of ABORTIVE ATTEMPTS is not limited to writers, of course. You may recall from the book the photo of Beethoven’s manuscript for his cello sonata:

And artists? Here’s Adoration of the Magi by Leonardo daVinci:

Unfinished, and you can see his sketches, none of which are particularly decisive. Leo kept his options open as he concentrated on what he saw clearly, stepping back and making decisions about every vague sketch as he went along. (Read more about it here.)

The point is that we almost never MAKE THE THING THAT IS NOT in a tidy, linear fashion, even if we’ve spent years “thinking” about the project. Once we get it out of our head and into what we laughingly call Reality, it’s more likely to come in bits and pieces and completely out of order rather than not. Embrace that idea, of ABORTIVE ATTEMPT > GESTALT > SUCCESSIVE APPROXIMATION, and your work may not get easier, but it will get done.

Which reminds me, I really need to focus on The Beethoven Blueprint, don’t I?